Lyme in Maine on the Rise

By Bryan Rosner on May 5, 2008 in Geographic Incidence

The incidence of Lyme disease in Maine continues to increase, and the rate of increase in incidence this year is significant compared to previous years. While this might be partially explained by growing awareness of the signs and symptoms of early Lyme disease among healthcare providers, and in the public, it is also likely that the number of new infections is truly increasing.

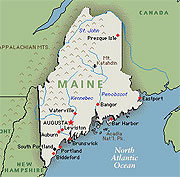

Most of the increases in reported incidence have occurred in southern Maine and in the midcoast. Some inland areas, including Kennebec County, have also experienced an upsurge in reported cases, a phenomenon that is consistent with ecological studies tracking changes in deer tick populations.

Lyme Disease Surveillance Report

Maine, 2006

Introduction

Lyme disease is a tickborne disease with variable dermatologic, rheumatologic, neurologic, and cardiac manifestations. The most reliable early clinical indication for the disease is an initial skin lesion commonly referred to as the ”bull’s-eye” rash or erythema migrans, which occurs in 70% to 80% of cases within a month after a tick bite. Untreated infections can lead to late manifestations in the joints, heart, and nervous system. Examples of these late manifestations include: arthritis characterized by recurrent, brief attacks of joint swelling; lymphocytic meningitis; cranial neuritis (such as Bell’s palsy); encephalitis; and second or third degree atrioventricular block.

Methods

Lyme disease is reportable in Maine. For surveillance purposes, Lyme disease is defined as:

- A person with erythema migrans; or

- A person with at least one of the late manifestations mentioned above and laboratory confirmation of infection. [Guidance on lab tests can be found at: www.MainePublicHealth.gov]

The Maine CDC investigates and collects surveillance data on reports of Lyme disease. Data presented in this report reflect only those reports that meet the case definition. Maine-specific data presented here were extracted from the National Electronic Disease Surveillance System (NEDSS), a disease-reporting database. National level data are obtained from Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports (MMWR). Population denominators are based on 2000 census data.

Results

During 2006, a total of 338 confirmed cases of Lyme disease were reported to the Maine CDC. This represents an overall case rate of 26.5 per 100,000 population. Consistent with state and national data from previous years, physician-diagnosed erythema migrans was reported in about 73% of cases. Fifty-six percent of the cases were male. The median age was 45 years, with a range of 1 to 91 years. Five percent of cases were reported to have been hospitalized.

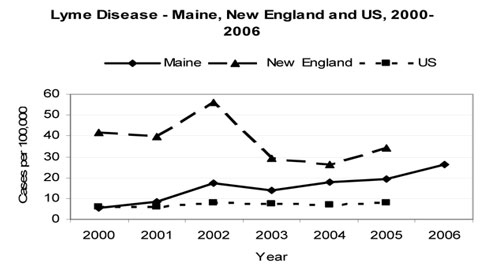

Five-Year Trend: The number of Lyme disease cases reported in Maine during 2006 is the highest since Lyme disease surveillance began in 1989; reported incidence here has increased steadily since 2000. Over the same period, incidence rates for the U.S. population have been relatively stable while rates for the entire New England region have fluctuated but still remain higher than for Maine.

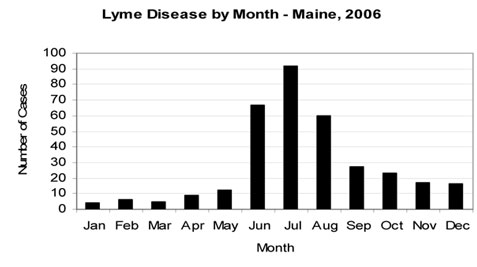

Distribution By Month of Onset: In 2006, as with previous years, peak incidence of Lyme disease occurred during the summer months. Sixty-five percent of all cases had reported onset in June, July, or August.

No cases were reported for residents of Aroostook County, Piscataquis County, and Washington County. York County and Cumberland County residents together accounted for nearly 68% of cases, at 133 and 96 cases, respectively. Case rates were highest for York County, Lincoln County, and Knox County (with 71.2 per 100,000, 56.5 per 100,000, and 42.9 per 100,000, respectively).

|

Lyme Disease by County – Maine, 2006 |

|||||

|

County |

Cases |

Rate§ |

Percentage |

||

|

Androscoggin |

10 |

9.6 |

3.0 |

||

|

Aroostook |

0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

||

|

Cumberland |

96 |

36.1 |

28.4 |

||

|

Franklin |

5 |

17.0 |

1.5 |

||

|

Hancock |

6 |

11.6 |

1.8 |

||

|

Kennebec |

22 |

18.8 |

6.5 |

||

|

Knox |

17 |

42.9 |

5.0 |

||

|

Lincoln |

19 |

56.5 |

5.6 |

||

|

Oxford |

1 |

1.8 |

0.3 |

||

|

Penobscot |

5 |

3.5 |

1.5 |

||

|

Piscataquis |

0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

||

|

Sagadahoc |

13 |

36.9 |

3.8 |

||

|

Somerset |

3 |

5.9 |

0.9 |

||

|

Waldo |

8 |

22.1 |

2.4 |

||

|

Washington |

0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

||

|

York |

133 |

71.2 |

|||

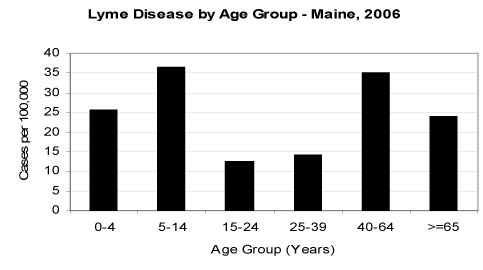

Case Rates By Age Group: Patient age is highly correlated with reported Lyme disease incidence in Maine. The highest case rates were observed among children between the ages of 5 to 14 years and adults between the ages of 40 to 64. Other high-risk groups were children under the age of five years and seniors 65 years and older. This is consistent with the pattern seen nationally, as well as historically in Maine.

Discussion and Recommendations

The incidence of Lyme disease in Maine continues to increase, and the rate of increase in incidence this year is significant compared to previous years. While this might be partially explained by growing awareness of the signs and symptoms of early Lyme disease among healthcare providers, and in the public, it is also likely that the number of new infections is truly increasing. Most of the increases in reported incidence have occurred in southern Maine and in the midcoast. Some inland areas, including Kennebec County, have also experienced an upsurge in reported cases, a phenomenon that is consistent with ecological studies tracking changes in deer tick populations.

Lyme disease case surveillance is less useful for ascertaining the absolute numbers of cases that occur than it is for identifying disease differences and trends across time, space, and demography. In this regard, the data this year can be interpreted to suggest two things. First, a slow but persistent diffusion of disease risk is continuing to occur, both eastward and into south central Maine. Second, real cases do occur as a result of exposures outside of the hyperendemic south coast, and that tick bite prevention messages need to reach persons who live and work in or engage in recreation in any potential tick habitat across the state.

The risk of Lyme disease can be reduced by avoiding tick-infested areas, using insect repellents containing 20% -50%DEET (for skin and clothing), and permethrin (for clothing only), and by checking for ticks – and promptly removing them – after returning from tick-infested areas. Deer herd management, landscaping interventions, and improved recognition of erythema migrans and other early symptoms of Lyme disease, will also help to reduce the burden that results from this infection.

Prepared by:

Anthony K. Yartel, MPH

Geoff Beckett, PA-C, MPH

Anthony.yartel@maine.gov

http://www.MainePublicHealth.gov

EPIDEMIOLOGY and ECOLOGY

Background: Although the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention does not provide clinical consultation on the management of individual cases of Lyme disease, the Medical Epidemiology Section in the Division of Infectious Disease receives frequent requests from health professionals for Lyme disease-related information to assist in patient assessment and care. This Health Advisory includes answers to some of the more frequently asked questions that we receive, and is not intended in any way to be comprehensive.

Summary: Maine has the 12th highest rate of Lyme disease among the U.S. states and its incidence has been increasing steadily since the late 1990’s. While the majority of cases occur among residents of southern coastal Maine , medical providers should be aware that the range of deer ticks in Maine has expanded gradually in recent years and that exposure to deer ticks and Lyme disease can occur in other areas of the state as well. Authoritative guidelines for the clinical diagnosis and management of Lyme disease and other tickborne diseases have been recently updated by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and links are available at the Maine CDC website: http://www.maine.gov/dhhs/boh/ddc/_lyme/lyme_1.htm

FAQ: Lyme Disease in Maine

1. Is the incidence of Lyme disease increasing in Maine ?

In Maine , the incidence of Lyme disease has increased steadily since the late 1990’s. In 2006, 338 reported cases were confirmed among state residents, an increase of 37% from 2005. While improvements in diagnosis and reporting may contribute to some degree, researchers and epidemiologists believe that there has been a real increase in disease incidence. Similar increases were seen in some other New England states during the same period.

2. What is the seasonality of Lyme disease in Maine ?

The great majority of cases of early Lyme disease have the onset of their symptoms during the summer months (June – August). A second, much smaller peak occurs in the fall (September – November), when adult deer ticks are active. Very small numbers of cases are seen during the winter and early spring (December – May).

3. Where are the highest incidence rates in Maine ?

About two-thirds of reported Lyme disease cases in Maine are reported among residents of York and Cumberland Counties , with the highest rates in southeastern York County . Over the past decade the numbers of cases have also been increasing steadily in areas of the midcoast (Sagadahoc, Knox, and Lincoln Counties ) and in the lower Kennebec river valley. The numbers of cases are generally much lower in the western mountains and in northern Maine . This distribution is consistent with ecological research on the distribution of deer ticks in Maine .

4. In what types of outdoor environments are deer ticks likely to be found?

“Potential tick habitat” is a term used to describe the type of environment preferred by deer ticks, and it includes woody or brushy areas and terrain with high grass and lots of leaf litter.

5. Should I consider Lyme disease in the differential diagnosis of a person with compatible signs and symptoms (e.g., erythema migrans-like rash) whose only recent outdoor activities have been in a “low incidence” area of Maine , such as Aroostook County ?

Yes. Even in areas where deer ticks are relatively uncommon and the numbers of Lyme disease cases are low, small foci of tick populations may present some risk of Lyme disease exposure to humans. By the same token, there are many areas of “potential tick habitat” in generally high incidence regions – such as coastal York County -where ticks are absent or sparsely distributed. It is reasonable to assume that there is at least some risk of Lyme disease exposure for persons who engage in outdoor activities in any “potential tick habitat” in Maine , especially during the summer and fall.

OTHER TICK-RELATED ISSUES

6. Do deer ticks in Maine carry infections other than Lyme disease?

Yes. While Lyme disease is by far and away the most common tickborne disease, deer ticks in Maine can also occasionally transmit babesiosis and human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA). These are described in the IDSA Guidelines (reference in the summary section, above) and also on other areas of the Maine CDC website section on tickborne infections. A close relative of the deer tick (Ixodes cookei, also known as the “woodchuck tick”) can also transmit Powassan encephalitis, a rare viral infection closely related to West Nile virus. Four cases of Powassan encephalitis were documented here between 2000 and 2004.

7. Do dog ticks in Maine transmit any diseases to humans?

In other areas of the country, dog ticks (Dermacentor variabili can transmit rocky mountain spotted fever (RMSF). In Maine , however, neither RMSF or any other significant human diseases have been documented to be associated with exposure to dog ticks.

8. Where in Maine can I send a tick to be identified?

The Maine Medical Center Research Institute (MMCRI) Vector borne Disease Laboratory in South Portland will identify the species of submitted ticks found on humans or pets. This is done free-of-charge. Ticks should be placed in alcohol in a leak proof container and sent to MMCRI per instructions that can be found at: (http://www.mmcri.org/lyme/submit.html).

DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT

9. Is laboratory testing necessary to support a clinical diagnosis of erythema migrans (EM)?

No. Serological testing during the first 2 weeks of infection is too insensitive to rule out Lyme disease. Erythema migrans – the expanding rash that occurs within 3-30 days of tick removal or detachment in about 70%-80% of Lyme disease cases – often occurs before a serological response has occurred. Thus, treatment decisions should be made on the basis of a clinical diagnosis based on physical examination and history (see the 2006 IDSA Guidelines referenced above, for an excellent and well-illustrated overview of EM) and should not depend on laboratory testing for confirmation. Laboratory testing, however, is a critical and necessary component of the evaluation of persons with possible Lyme disease-associated signs and symptoms other than erythema migrans.

10. What diagnostic tests are currently recommended for use in Lyme disease diagnosis?

In the absence of erythema migrans, both the Federal CDC and the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommend the use of two-tier serological testing, that includes a sensitive screening test (ELISA or IFA) followed by IgM and IgG Western Blot testing, if the screening assay is positive. Clinicians should be wary of non-validated test methods used by some commercial laboratories, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of blood, urine antigen tests, and lymphocyte transformation tests. Some laboratories also interpret Western blot tests using criteria that have not been validated and published in peer-reviewed scientific literature (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5405a6.htm).

11. Where can I find reliable guidance on current approaches to Lyme disease diagnosis and management?

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) released its detailed update of clinical practice guidelines for Lyme disease and other tickborne infections in late 2006. These can be downloaded from the Maine CDC website (www.mainepublichealth.gov).

PREVENTION

12. Does early tick removal effectively prevent Lyme disease?

Yes. The removal of an infected deer tick within 36 hours of its attachment will prevent transmission in most cases. Perhaps the most important component of Lyme disease prevention is performing daily tick checks after spending time in potential tick habitat, and removing any ticks that may have become attached.

13. What are the current recommendations for the use of tick repellents?

For application to uncovered skin, the federal CDC currently recommends the use of insect repellents containing a 20%-50% concentration of DEET for the prevention of tick bites. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that repellents containing up to 30% DEET can be used on children > 2 months of age. DEET concentrations in this range will provide protection for 5-8 hours against both ticks and mosquitoes. Data on the tick prevention effectiveness of picaridin, an effective alternative to DEET for prevention of mosquito bites, is currently limited. Permethrin, which is sold in spray and liquid forms, can be applied to shoes, socks and outer clothing (but not directly to skin), and kills ticks on contact. After an application, it will remain effective through several washings. It is also effective in preventing mosquito bites.

14. How do I report a case of Lyme disease to Maine CDC?

Lyme disease case reporting forms can be downloaded from the Maine CDC website and faxed or mailed to our office. Remember that it is especially important to report cases of clinically-diagnosed erythema migrans (EM), and that laboratory testing is not required to confirm a case of EM.

15. What is Maine CDC doing to increase public awareness about Lyme disease prevention?

Although there is currently no dedicated federal or state government funding for Lyme disease education and prevention, Maine CDC has worked with community partners for several years doing this work within existing resources, including developing and disseminating educational materials, assuring that information on Lyme Disease is presented at some annual medical and public health meetings, and maintaining a website dedicated to tick borne diseases in Maine. Maine CDC recommends that health education efforts utilize a “universal tick hygiene” approach that includes recognition of typical EM rashes, the proper use of insect repellents, and an emphasis on the importance of tick checks and early tick removal after work or recreation in tick habitat (whether or not it is in a high incidence area of the state). Existing materials can be found and downloaded at www.mainepublichealth.gov.

| Name of Support Group: | Eastern Maine Lyme Disease Support Group |

| Contact Person for this Group: | Happy Dickey RN |

| Contact Person Telephone: | 207-862-2444 |

| Contact Person E-Mail: | cdickeyrn@midmaine.com |

| City: | Bangor |

| State or Province: | Maine |

| Country: | USA |

| Regions of your state / province served by this group (i.e. south-east Pennsylvania): |

Eastern and northern Maine |

| Your Name: | |

| Your E-Mail Address: | |

| Other Information: | Meetings are the second Monday of the month from 1pm to 3pm at Eastern Maine Medical Center. |